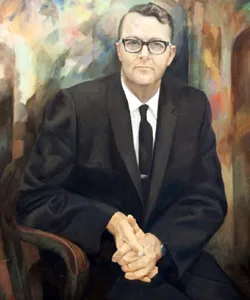

Aden Meinel: Astronomer, Optical Scientist, Founder and Scholar

Aden Meinel was the founding director of the University of Arizona Optical Sciences Center and the Kitt Peak National Observatory. With his wife and research partner, Marjorie, he also developed next-generation space-telescope concepts and pioneered the use of solar energy.

When Steve Jobs, cofounder of Apple Inc., died last year, millions mourned. Everyone who owned an iPod, iPhone or iPad took a moment to memorialize an innovative inventor who lost a long battle with pancreatic cancer.

But three days before Jobs died, on 2 October 2011, another innovative intellect breathed his last: Aden Meinel—astronomer, engineer and optical scientist—passed in his sleep in Henderson, Nev., U.S.A., at 89. Although fewer headlines noted Aden’s death, anyone who has benefited from solar energy or marveled at a stunning Hubble-telescope image of the universe has been touched by his legacy.

Early Life

Aden was born in Pasadena, Calif., on 25 November 1922. According to close friend James B. Breckinridge, the Meinels came from eastern Pennsylvania, with roots in Germany. A search for work brought the family to California. There, Aden’s technically trained father, unable to find a position that utilized his skills, became a handyman and house painter to support the family.

Aden, the youngest of three stepbrothers, always took to mechanical things. He built his own toys with woodworking tools and was placed in advanced classes when he started school. In 1940, in an 11th grade accelerated math program at Pasadena Junior College, he started dating a smart, strong-willed young astronomer named Marjorie Pettit; she would, in time, become his coauthor, editor and partner in life.

At Marjorie’s urging, Aden changed his college major from aeronautical engineering to astronomy, so they could share classes. Aden also volunteered with nearby California Institute of Technology’s physics department, researched Venus’ atmosphere alongside graduate students and served as an apprentice optician at Mount Wilson Observatory.

The Great Depression was waning, and World War II was driving research on any subject with military significance. As Breckinridge noted in a presentation on the occasion of Aden’s 80th birthday, “there had been no more exciting time for applied sciences” since the Dark Ages. Meinel was fully immersed in it.

College, Military Service, and Beyond

Aden was admitted to Caltech in 1941 as a sophomore while Marjorie studied at the University of California, Berkeley.

Aden apprenticed at Roger Hayward’s optical fabrication lab, where he learned to make aspheric plates for Schmidt cameras. This work would inspire him to study Schmidt plates for his doctoral dissertation.

However, after the United States entered World War II, Aden knew he would need to serve in the military. In the spring of 1942, he joined the V-12 Navy College Training Program, in which he worked under future Nobelist William Alfred Fowler.

He joined a highly classified rocket project and worked on training, timing, trajectories and fuses—including the time-delay fuses for what would become “the Gadget” at the first test detonation of a nuclear device. When Marjorie finished her master’s degree at Claremont College in 1944, she joined him on the rocketry team.

In 1944, the pair married. Unfortunately, a draft notice was waiting for Aden when they returned from their honeymoon at Kapteyn Cottage, a guest house on Mount Wilson that was built for and named after a visiting astronomer.

Thus, Aden spent his 22nd birthday in Navy boot camp in San Diego. His group was scheduled to serve on the brand-new ship, the U.S.S. Indianapolis, which lay across the bay; they were excited at the prospect of clean bunks and regular showers.

Other orders came for Aden, though. He reported back to the Navy office at Caltech and was commissioned as ensign at the China Lake Navy ordnance research station soon after. A different fate met his friends on the Indianapolis; the ship was torpedoed on its way to Manila. Many of the explosion’s survivors died of exposure, dehydration and shark attacks in the worst single loss of life in Navy history.

Six months after he was drafted, Aden found himself in Hingham, Mass., at munitions school. Within a month, he was in Europe, assigned to Patton’s 3rd Army as a rocket and optics expert. His job was to hunt out Germany’s optical and ballistic technology, while also helping scientists and technicians from some of the world’s best optics companies head to the West.

Aden’s childhood fluency in German served him well on the Western Front. In one foray, he found a note signed, “A. Hitler” that was written in what he described as “a nice script.” The page, which he had found windswept in a burned-out director’s office, was marked geheime kommandosche, or “top secret;” it held a list of the Third Reich’s highest priority rocketry and guided missiles programs, one of which was called schmetter- ling, or “butterfly.” Later, while exploring the Nordhausen rocket factory in Jena, Aden saw two big crates, both marked schmetterling, that held advanced cruise missiles.

Due to an administrative mishap, Meinel never received the awards he’d earned for his service under fire with the 3rd Army. In fact, there was no official record that he’d ever been to Europe. But “the bullets were real,” he said. “I slept in bombed-out buildings out in the open just like any GI.”

Fortunately, upon his 1946 return, he did receive a large check for the per diem pay he’d accrued while on the front. It paid for the Meinels’ first car.

Now back on familiar soil, Aden sought to complete his studies. Caltech wanted him to complete three more semesters before allowing him to start graduate school; the battle-hard- ened naval officer found a better deal at UC Berkeley. There, he was allowed to earn his bachelor’s degree as soon as he finished the requisite tests.

Aden received his bachelor’s from UC Berkeley in 1947, and then his Ph.D. in 1949—finishing his graduate studies after only two years. For his dissertation, he designed the world’s first solid Schmidt spectrograph, through which he viewed chemiluminescence in the night sky.

After Berkeley, the Meinel family moved north. Aden served as a research associate at the University of Chicago for two years before he became an associate professor. In 1953, he was named associate director of Yerkes and the McDonald Observatory, a position he held for three years. He recorded, analyzed and explained hydroxyl emission bands in the night sky, now called Meinel bands, while working at Yerkes.

To read the article in its entirety, download the PDF.