Reflections: Arvind S. Marathay

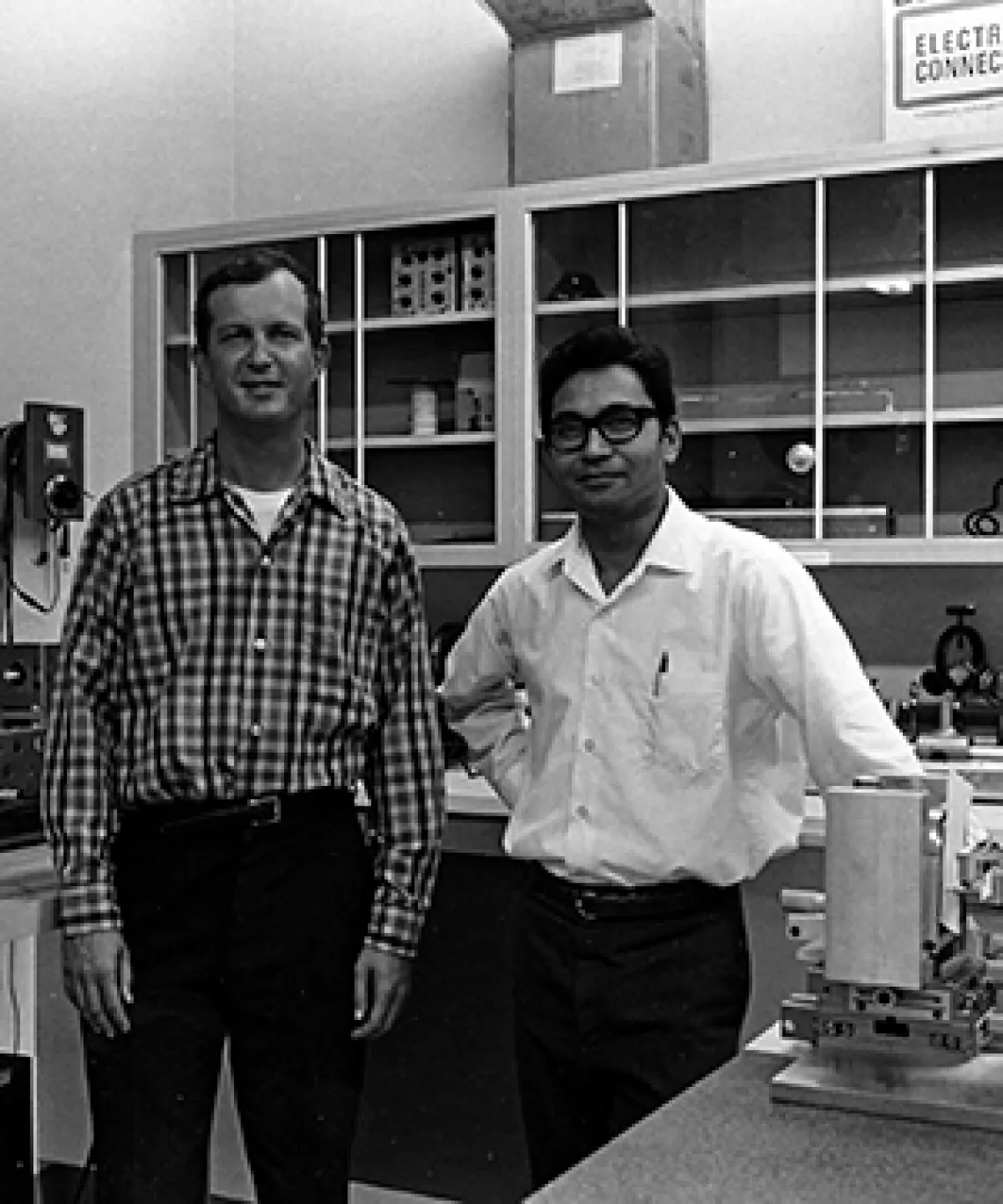

Fred Hopf and Arvind Marathay

Ask any student what makes the Wyant College of Optical Sciences special and chances are they will mention a professor—someone who has inspired or challenged them, helped them develop a passion, or simply been a friend. Professor Emeritus Arvind S. Marathay embodies all of those qualities and more. Not only is his resume impressive, but the genuine extent to which he cares for the students and the College sets him apart.

For many reasons, one of the professors who impressed me the most was Professor Arvind S. Marathay, who taught a course in physical optics in the 1970s. The combination of lectures, homework problems, classroom demonstrations, and tests made his class very interesting. The range of topical areas covered in professor Marathay’s presentations made a great impression on me.

(William H. Swantner, ’78 Ph.D., Optical Sciences Center)

Born 11 Dec. 1933 to Shankar and Anasuya Marathay, Arvind grew up in Bombay (now Mumbai) India. His father was a medical practitioner who specialized in women’s health. Known to be extremely clever and enterprising, Arvind’s father was also one of the first in India to prescribe and make contact lenses for his patients.

Your father once had a very famous patient. Can you tell me about that?

By the 1970s, going to the movies was one of the most popular forms of entertainment in Bombay, and one of the most popular films was “Pakeezah,” starring Meena Kumari. Depicting the struggle of Indian women in the 1950s and 60s, Kumari played both the roles of Nargis and her daughter, Sahibjaan. Portraying Nargis required the actress to wear a bronze wig and grey contact lenses. My father was asked to make those lenses for Kumari.

Your family name was originally Marathe, but your father changed it to Marathay. Why?

Always practical, my father thought the spelling of the name should reflect the pronunciation.

1947 was an eventful year in India as it became independent from the British crown, resulting in the split of India and Pakistan. How did this affect your family?

It was a confusing time in India. On one hand, it was a time of great nationalistic pride—on the other, it was a time of great sadness due to the trauma of Partition and, later, the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948.

You attended Jai Hind College, affiliated to the University of Bombay, to study physics. Can you tell me about that choice?

Jai Hind College was established in Bombay in 1948, just after independence, by a small group of teachers who were displaced from D. J. Science College of Karachi, Pakistan. It started as an Arts and Sciences College, and I felt I would be able to obtain a well-rounded education there.

After graduating from Jai Hind College in 1954 with a B.S. in Physics, why did you choose to leave India and go to the United Kingdom for your master’s degree?

Planning to eventually return to India to work with my father as a lens designer, I chose to pursue my master’s degree at Imperial College London, well-known for its Optical Design Department.

How did that plan work out for you?

Very well for me, but not as well for my father. At Imperial College I realized I was not nearly as practical as my father. I was far more of a theoretician. I had the great fortune to study under two physics greats, H.H. Hopkins and Walter Weinstein (Welford). I was influenced greatly by both.

You were at Imperial College at the same time as another OSC emeritus professor, Nick Stravroudis. Did you know him at the time?

Yes, although I graduated with my master’s degree a couple of years before Nick graduated with his Ph.D., we knew each other. He was a true gentleman and we spent many enjoyable evenings discussing mathematical effects. We kept in touch after graduation, even after he came to Arizona to join the Optical Sciences Center (OSC). He was one of the reasons I later joined OSC myself.

After receiving your M.S. degree from Imperial College in 1957, you moved to the States to pursue a Ph.D. in Physics at Boston University. How did you choose Boston University?

Professor F. Dow Smith, from Boston University, read a paper I had published, outlining a geometrical optical interpretation of the performance of lenses. Professor Smith forwarded the paper to his colleague Ed O’Neil and professor O’Neil sent me a letter to offer me a graduate assistantship in Boston.

Was moving to the United States an easy transition for you?

Yes, it was surprisingly easy—probably because I had just spent the last three years in London. The only peculiarity was the looks I received as an Indian with a strong British accent.

You became a United States citizen while in Boston. Did you and your wife, Sunita, become citizens at the same time?

No, Sunita received her citizenship one year before me, then encouraged me to do the same. She was always a couple of steps ahead of me.

After receiving your Ph.D. in 1963, you worked in industry for a few years, accepted a postdoctoral position at the University of Pennsylvania, then returned to industry. In 1969, you joined the faculty of the College of Optical Sciences at the University of Arizona as an associate professor. What prompted you to leave industry and become an academic?

While I was a Ph.D. student at Boston University, then a postdoc at the University of Pennsylvania, I realized I enjoyed my teaching assistant positions much more than my research assistant positions. After spending a few years in industry, Nick Stravroudis suggested I come to OSC. I was excited about the possibility of returning to teaching, and the wild-west persona of Arizona—that I saw portrayed in Western movies—intrigued me.

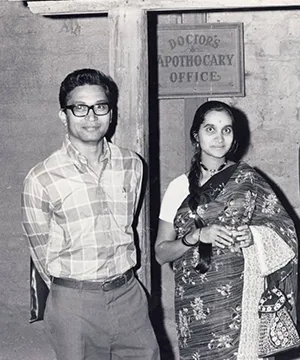

Arvind and Sunita Marathay, 1971 OSA Meeting, Old Tucson

I have met several University of Arizona alumni who have told me that you and Sunita played the role of welcome committee to many Indian students in the 1970s. What led you to do this?

In the early days of my academic career, it was uncommon for there to be students from India at the University of Arizona, and there were no groups on campus to help their transition. Sunita would find out through our friends and acquaintances that a new Indian student was arriving, and she would be one of the first to invite them to our house for a traditional meal and friendly conversation. I think her efforts were greatly appreciated.

You taught some very challenging material in your courses, but had a reputation for making complex subjects understandable. What were your strategies for doing that?

That is a very nice compliment. I don’t feel that I did anything special, but I strived to create a comfortable classroom atmosphere, encouraging interaction with my students. I always tried to be approachable if a student needed any additional clarification. Mostly, I feel that I was very fortunate to have taught such excellent students!

What led you to write the book, Elements of Optical Coherence Theory in 1982?

By the early 1980s, the theory of partial optical coherence was evolving, and there was a need for a textbook to introduce students to the basic elements of partial optical coherence. I felt there should be a practical handbook, enabling students to master the fundamentals, and apply its methods to their own fields of interest. Drawing from the lecture notes of courses I had taught, I included worked examples, homework problems and literature references. My goal was to encourage more advanced study.

What was your favorite paper that you wrote and had published?

I would have to say that my favorite paper was one I wrote while working at Technical Operations Research in Mass., “Realization of Complex Spatial Filters with Polarized Light” [JOSA, vol. 59, Issue 6, pp. 748-752 (1969)]. I was the first to describe making complex spatial filters using the properties of polarized light and Polaroid Vectograph film.

Can you tell me about your involvement with the Optical Society of America (OSA)?

I served as Chairman of the Tucson Section of OSA from 1978-79 and I am an elected Fellow of the Society.

In a September 1979 issue of OSCillations, I saw mention of you visiting OSC alumnus Ming-Wen Chang (Ph.D., 1975) in Taiwan. Can you tell me about this trip?

After an extended visit with my family in India, I traveled to Taiwan for a lecture tour arranged by Ming-Wen. We traveled across Taiwan by train, visiting various universities. I talked a lot (seven or eight lectures) and saw a lot of interesting sights. The best was the National Palace Museum in Taipei—a beautiful museum with amazing Chinese imperial artifacts and artworks.

After retiring from the University in 2002, you and Sunita established the Marathay Family Endowed Undergraduate Scholarship in Optical Sciences (Left Picture: Arvind and Sunita Marathay, 2014 OSC Scholarship Award Ceremony). After working primarily with graduate students for over 30 years, why did you choose to support undergraduate students?

Sunita and I felt that there are fewer funding opportunities for undergraduate students interested in studying optics. It was our hope that this scholarship would help a student—at the beginning of their academic endeavors—explore the wide variety of research areas that OSC offers. So far, 10 scholarships have been awarded, and I have truly enjoyed meeting each of the students. The field of optics is in good hands.

D. Kim, J. Wyant, V. Mahajan, A. Marathay, 2019

What activities are you enjoying now that you are retired?

I have more time now to visit my son, Preshant, in San Jose and my daughter, Geetika, in Boston. I am very lucky to have five wonderful grandchildren, Ranjit, Sitana, Anika, Riana and Viena. I also try to come into OSC once a week—usually for Colloquium. I think it is very important at any age to keep trying to learn new things and, as a retired university professor, it is easy to find many opportunities to stay engaged.