Reflections: Stephen F. Jacobs

I first discovered the workings of Professor Emeritus Stephen F. Jacobs before I actually met the man. New to Tucson, I was pleasantly surprised to find my footsteps bathed in all the colors of the rainbow while strolling through downtown on a typical sunny day. Later, while walking that same path with Steve, he confided to me that 60 years after receiving his Ph.D. in Physics from Johns Hopkins University, he had “finally” identified his niche in the field of optics — "turning people onto science by letting science speak for itself, through art and outreach."

Since that day, I have had many opportunities to walk and talk with Steve, and when I began writing this biography, I found myself caught up in his enthusiasm for optics and life.

Early Life

Born October 1, 1928 in New York City, New York to Henry and Josette Jacobs, Steve grew up in Greenwich Village with his older sister, Judy, until 1938 when the family moved to Long Island City. His father was a Colombia University trained civil engineer, but one of Steve’s most vivid memories is of him candling and peddling eggs during the Great Depression. After his father’s death in 1940 and his grandmother’s death two years later, Steve’s mother moved the family to Manhattan to live with his grandfather Leo Frank.

Steve’s path to a career in optics began as an intense need to understand the world around him. Light and color reached out to him, begging to be understood. He has always considered his journey atypical of his peers, stating that he "had no special talent — was good at math and physics, but not exceptional." As a teenager at McBurney School, a college preparatory school in Manhattan, Steve was known as king of the game room, mastering games of strategy such as chess and pegity. When it came time to choose an undergraduate college, Steve followed in his sister’s footsteps and spent his undergraduate years at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio — hoping their Cooperative Education Program would lead him to a career.

The summer before his junior year, Steve still had no clear idea of a career path as a physics major, but did know he wanted to explore the Southwest. So, he took a bus to New Mexico, hoping to talk his way into an interesting co-op position. Steve ended up at New Mexico School of Mines in Socorro, working alongside a technician instrumenting what happens to the stabilizing sabot of a cannon after discharge from the launch tube. Ideally, the sabot would separate from the projectile without disturbing the flight of the projectile and without creating a hazard to personnel in the immediate area. It was their job to figure out how to increase those odds.

After receiving his B.S. in Physics, and still not sure of what he wanted to do when he grew up, Steve decided to pursue a graduate degree in physics. Throughout his years at Antioch, he had most admired his physics professor, Al Stewart, who had studied under Professor Gerhard Dieke at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Again, following in footsteps of those before him, Steve began his Ph.D. program of study at Johns Hopkins under Professor Dieke. After "five of the most miserable years of [his] life," he was awarded a Ph.D. in Physics. Steve has always felt that degree was given to him mainly on the merit of his teaching skills.

Early Career

Upon graduation, Steve’s first thought was to join academia. The Physics Department at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, offered him $4,400 a year as an assistant professor. Not totally happy with the salary, he decided to delay becoming an academic. Instead, he accepted a position with Perkin-Elmer Corporation in Norwalk, Connecticut where optical engineers were working on exciting projects, such as the Baker-Nunn Satellite Tracking Camera. Steve worked alongside fellow Professor Emeritus Roland Shack from 1957 to 1959, becoming great friends with Roland and his wife, Pam.

By 1960, Steve was looking for a new job. He got lucky at the Physical Society meeting in New York City when someone, who knew he was trained in spectroscopy at John Hopkins, introduced him to Gordon Gould of the Technical Research Group (TRG). Gordon was looking for a spectroscopist to demonstrate his 1957 teachings — "How to Build an Optical Amplifier." He had recorded his analysis and suggested applications in his laboratory notebook under the heading "Some rough calculations on the feasibility of a LASER: Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation." This notebook, which Gordon had notarized, contained the first recorded use of this acronym.

With funding from the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), Gordon was able to hire Steve and Paul Rabinowitz. Unfortunately for Gordon, the government declared the project classified, which meant that a security clearance was required to work on it and, due to his former participation in a Marxist study group in the 1940s, Gordon was unable to obtain a clearance. So, it was up to Steve and Paul to demonstrate his teachings. They succeeded in measuring light amplification in 1961 and in building a laser oscillator in 1962. On the basis of these, Gordon eventually won the basic laser patent after a 30-year legal fight and became a rich man.

Gordon and Steve remained friends until his death in 2005. In fact, Steve laughs about Gordon accompanying him on a portion of his honeymoon in Switzerland after he married Kathleen "Kathy" Mitchell in 1963. (Their honeymoon just happened to coincide with the 3rd International Quantum Electronics Conference in Paris, where Steve presented the optically pumped cesium laser results with Gordon in attendance.)

Academia

Around this time, TRG was purchased by Control Data Corporation and Steve began looking for other employment. Roland Shack invited Steve to join him, Bob Noble and Aden Meinel in Arizona. So in 1965, Kathy and Steve left Connecticut for Tucson and he became the Optical Science Center’s (OSC) first "laser man in the desert."

With the invention of the laser, came a flood of new developments in the field of Quantum Electronics. By the late 1960s, there was much to be learned, but not any formal courses. Recognizing this need, Steve and Marlan Scully — then at MIT, but later at OSC (1969 to 1980) — organized a series of two-week summer schools that later evolved into advanced Physics of Quantum Electronics (PQE) workshops and technical progress reports. Marlan handled the marketing, designed the technical programs and invited the speakers. Steve and Kathy managed the logistics for fun and profit until the mid 1990s.

They were the first to discover the winning combination of learning, skiing and the opportunity for participants to interact with funding agencies. As an added bonus, these meetings proved to be an effective way to recruit world-class optical physics faculty, including OSC’s second director, Peter Franken. To this day, Marlan, now at Texas A&M, is still very involved and PQE meetings remain highly successful.

In the early 1970s, science and industry had an increasing need for optical materials that were dimensionally stable over wide ranges of temperature and time. With the precision made possible by laser interferometry, it was possible to observe the daily length changes of even the most stable metals maintained at constant temperature. Until 2009, Steve’s OSC laboratory was effectively a National Bureau of Standards for dimensional stability of materials for optical engineering.

Successful collaborative projects included determining quartz homogeneity for the Gravity Probe B relativity experiment; working with Roger Angel, Steward Observatory Mirror Lab, to identify the most homogeneous glass for spin casting; assisting NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in the development of ultra-stable Invar 36 for the Cassini spacecraft; and unpublished calibration of Corning Inc.’s measurement system.

Sharing the Joy of Optics

Sharing his excitement for optics has always been Steve’s motto from the beginning of his career. As a kid growing up in New York City, he was fascinated with the Museum of Science and Industry. "It had all these push-button displays that you could go in and play with. It was great. I had wanted to construct something like that ever since."

So in 1973, Steve built 20 interactive optics exhibits on a shoestring budget, with the help of senior citizens and students. Arranged in a donut fashion around the OSC test tower, the theme of the display was "What is Light?" Visitors pushed a button to turn on the different lights in the electromagnetic spectrum; pulled a lever and watched their mirror image be distorted and then restored; and used light beams to talk over the telephone. The main objective of this exhibit was to stimulate an interest in light and optics, especially in younger people. A secondary benefit was the representation of areas of activity at OSC.

In 1996, Steve moved on to an even bigger project when he mounted a 50-ft diffraction grating on the roof of Tucson City Hall, resulting in what Steve has always considered as one of those times when being "scooped" turned out to be a good thing. It just so happened that in 1987, in commemoration of the 1887 Michelson-Morley Experiment, the sculptor Dale Eldred mounted a 53-ft plane diffraction grating atop Crawford Hall at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio. The diffraction grating was beautiful, but the colors were too directional and too brilliant. A viewer had to be in just the right place to see the colors, and then they were too intense for eye comfort.

Steve figured out a way to send the light in all directions by attaching diffractive material to a wavy surface made of corrugated steel. The diffraction grating spread the colors horizontally, while the wavy substrate was oriented to spread the light vertically by virtue of geometric optics. The colors reflected from the top of City Hall are still widely visible all over downtown Tucson — bathing the footsteps of many in all the colors of the rainbow.

Life After OSC

Although Steve has been retired from OSC since 1996, he still fills his days with many active and creative endeavors. When not busy with his and Kathy’s three children and six grandchildren or with maintaining their expansive garden, Steve enjoys a lifelong love of tennis — playing six days a week on his home court. (Two of those days are scheduled lessons so that he might, at the age of 87, improve his serve!)

And, of course, optics is still a part of his everyday life. "Some people may think I’m crazy, but I love this stuff!" Recently, Steve made a timeline of a few of his favorite optics art projects he completed over the years. His hope is "to inspire others to always see beauty in the ordinary."

The Optics Art of Stephen F. Jacobs

Rainbow Over Salad Bar, University of Arizona Student Union, 1989.

For more on this piece, read the Roy G. Biv Visits the Union Club Light Moments article.

Folding Along a Curve, 8th floor OSC and Jewish Community Center, Tucson, 1990.

For more on this piece, read the Folding Outside the Straight Line Light Moments article.

Wavy Gratings Atop Tucson City Hall, El Presidio Park and Entrance of Flandrau Science Center and Planetarium, University of Arizona, 1996 - 1998.

Read more about Wavy Diffraction Gratings.

Kitchen Optics, 5th floor OSC, 1999.

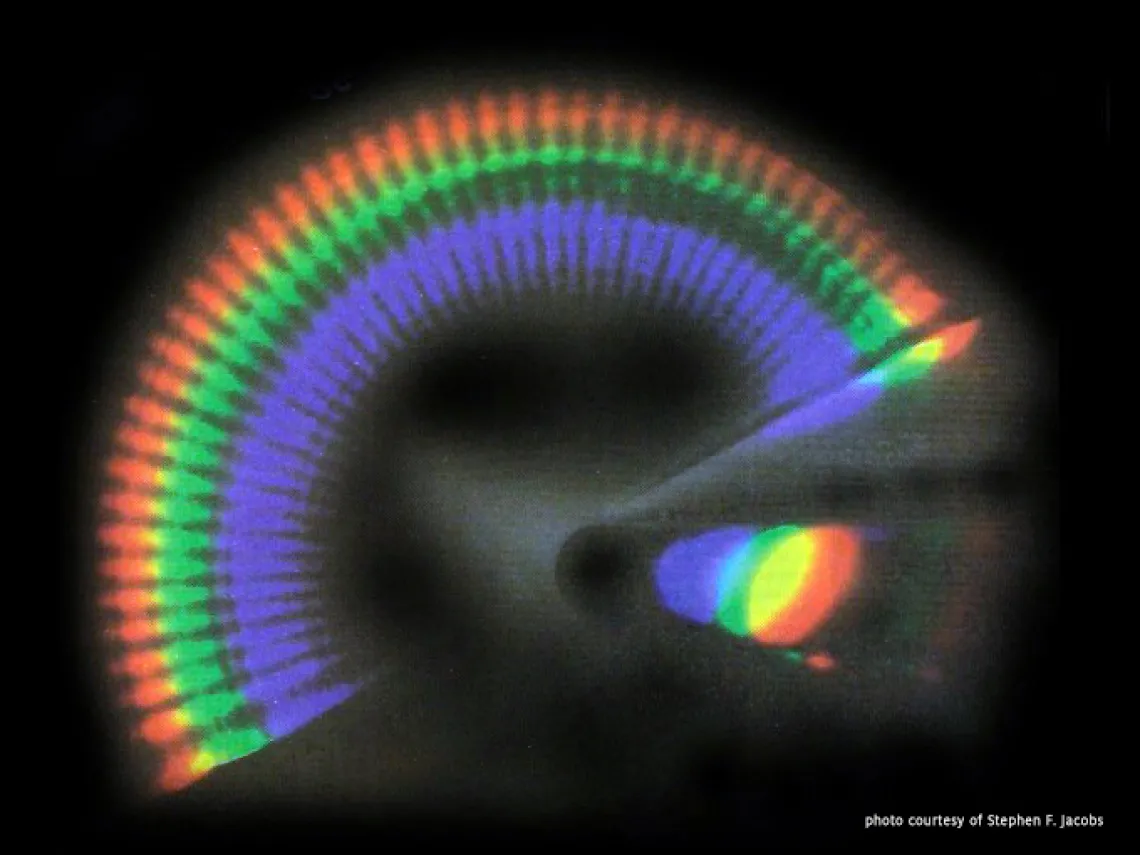

"One day my wife called me into her kitchen to look at a beautiful light pattern on her white refrigerator wall. What caused it? A real puzzler! It wasn’t hard to learn the origin of the spectral colors: a small prism, sunlit in the kitchen window, produced the spectrum. The spectral colors were reflected off the polished curved cylindrical surface of the granite counter top. But what caused the fan of radial black lines, or spokes?

Close examination by a magnifying loupe revealed the answer: periodic unpolished lines. The flat surfaces reflected the colors, but periodically nothing was reflected, resulting in the black spokes.

It turns out that cylindrical surfaces are difficult to polish. I deduced the cylindrical shape was produced by frequent passes of a grinder and then polished as flat surfaces.

I took the picture to Granite Creations, the folks who made the granite counter top, and asked whether the cylindrical surfaces were made by multiple flat passes. The answer was yes."

- Stephen F. Jacobs

Sun Clock, Kitt Peak Museum, Tucson, 2005.

"In 1959 I attended the ICO 5 meeting in Stockholm, Sweden. Perkin-Elmer had sent me to talk about the fast far-infrared photodetectors I was making for antisubmarine warfare. We were treated to a visit to Stockholm Observatory where I fell in love with their beautiful sunshine recorder … a polished glass sphere that focused sunlight to a point that charred a paper strip recording the sunny hours.

Forty years later, I wanted to make a clock instead of a recorder … just as beautiful. A demonstration at The Desert Museum in Tucson attracted enormous tourist attention. 'It turns the world upside down,' they gasped. Instead of the Desert Museum, my sun clock wound up atop Kitt Peak at the visitors center."

- Stephen F. Jacobs

Diffractive Fish in Sea of Cortez, Photo - 4th floor OSC, 2013.

"Over the years, I have had a lot of fun exploring folding along a curve, especially sine curves with various relative phases and amplitudes.

Then one day I discovered I could make a fish by extending the sinewaves. In 2013, my family was in Mexico by the Sea of Cortez with time on our hands. So I constructed a cardboard fish, sealed it with tape and set it loose to sink or swim while we hastened to snap some pictures. We had about 2 minutes before the fish began to sink!"

- Stephen F. Jacobs

Giant Polished Glass Sphere, OSC lobby, 2014.

Read more about the Giant Glass Sphere.