Reflections: Arthur Francis Turner

Imagine a car with a color-shifting paint job, changing from green to purple to gold, depending on the viewing angle and availability of light. If you were lucky enough in 1996, you may have done more than imagine the possibility — you may have witnessed the first car to feature color shifting technology. That year, Ford Motor Company introduced 2,000 Mystic Mustang Cobras, featuring a high-tech paint with ChromaFlair, a color-shifting pigment. At the time, this technology was considered groundbreaking.

But, for every groundbreaking invention, there is most likely a forward thinker, well ahead of his or her time. Forty years before JDS Uniphase Corporation's Flex Products Group created ChromaFlair, Francis Turner had explored ideas for incorporating thin-film coating flakes into paint to create angle-shifting colors. He envisioned a "getaway car," where the bank guard would say, "There goes that red — no, green — no, blue car," as the angular shift changed the color. In the intervening years, Francis freely shared his ideas — and notebooks documenting them — with other "thin-filmers," including then-M.S. student, Len Mott.

That level of creative thinking is one of the reasons Professor Emeritus Arthur Francis Turner (1906-1996) has been referred to as, "the father of optical coatings," and why in 1988, at the Topical Meeting on Optical Interference Coatings in Tucson, he received a standing ovation from his peers, while being honored as an "industrial pioneer."

Early Life

Arthur Francis Turner was born in Detroit, Michigan in 1906. After graduating in 1929 from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) with a B.A. in Physics, he headed to Germany to pursue a Ph.D. in Physics at the University of Berlin with Professors Peter Pringsheim and Marianus Czerny.

Francis once explained that the general practice in Germany at that time was to list authors in alphabetical order in publications. As a result, many professors would not accept students whose name came earlier in the alphabet. "But," clarified Francis, "with my surname beginning with the letter T, I more or less had my pick of advisors."

Even with the advantage of his "late in the alphabet appearing" last name, Francis admitted that, as a research fellow, he found giving seminars particularly daunting — due to the fact that the front row typically seated not only Czerny, but Nernst, Planck and Einstein!

Czerny-Turner Spectrometer

In 1930, Francis published a paper with Czerny pointing out the aberration corrections inherent in the now famous Czerny-Turner spectrometer mounting. This work was largely forgotten until the Ebert-Fastie system was rediscovered in 1952.

Several years passed before anyone realized that the Czerny-Turner design offered an even greater opportunity for aberration correction than the Ebert-Fastie mounting, through utilization of two smaller spherical mirrors.

Early Career

After being awarded his Ph.D. in 1935, Francis accepted a teaching position at his alma mater, MIT. There, he initiated pioneering research on optical interference coatings with C. Hawley Cartwright, whom he first became acquainted with in Professor Czerny's laboratory.

In 1936, John D. Strong published an article on evaporating calcium fluoride for antireflection purposes. This led Cartwright to want to pursue the matter, and he enlisted Francis's help in 1938.

We were both instructors in Donald Stockbarger's lab course at MIT and had a tiny Hg-pump vacuum system available. It was primarily used for student instruction. We used lithium fluoride at first because there was so much of it around. At that time, professor Stockbarger was perfecting his crystal-growing furnace and produced lots of large synthetic LiF boules, which, as I remember, were free for the asking. Then, one day I happened to chance on a bottle of magnesium fluoride, and you know the rest of the story. [Magnesium fluoride quickly became the material of choice for antireflection coatings.] (Reminiscences: from the files of A. Francis Turner, OPN March 2006)

With the use of A.C. Hardy's recording spectrometer, their thin-film work rapidly progressed from antireflection coatings to quarter-wave stacks. A collaborative publication in 1939 described some of the earliest work on stacked quarter-wave films as interference coatings.

In late 1939, Francis joined Bausch & Lomb Optical Company (B&L) in Rochester, NY as head of the Optical Physics Department. Under his leadership, B&L led the field of optical coatings for at least two decades.

B&L During WWII

When Francis began at B&L, the optical thin-film coating industry did not exist, but he directed his department toward antireflection coatings. It had become obvious in the early days of World War II that coated binoculars could be used much more effectively in low light than uncoated ones — and, hence, the coating industry was born.

The group's breakthroughs included methods for designing and manufacturing multilayer film stacks using ZnS, Cryolite or MgF2. These stacks were used as antireflection, narrow bandpass, long- and short-wavelength cutoff filters and suppressed-side-band filters.

Francis was involved in the first use of evaporated films as antireflection coatings in the United States, and he developed numerous coatings for military operations. The first commercial use of these antireflection coatings came later in drive-in movie projectors made at B&L in the 1940s.

When the epic Technicolor film "Gone with the Wind" first premiered, the prints were too dark to be seen well in outdoor theaters. To improve the amount of light getting to the screen, one of the multi-element projector lenses was disassembled and various individual lenses were given MgF2 AR-coatings — increasing the brightness substantially. Today, you won't find any precision lenses — such as those used in cameras, telescopes or in science and industry — without an AR coating. "After all, tomorrow is another day!" (Scarlett O'Hara)

B&L After WWII

After the war, Turner's group at B&L was largely responsible for adapting transmission-line theory (previously developed for microwave research) to compute the optical behavior of films. This discovery was of great importance in the thin-film field and Francis became a dedicated teacher of this new computational technique. Without it, very little progress would have been possible in multilayer-filter design.

During this period, his laboratory turned to the development of interference coatings for the infrared region. Francis developed the prototype design for the multiple-cavity-type bandpass filter. He also published the first known work on the effects of mechanical stress in optical coatings, and introduced the concept of stress compensation.

And the Oscar Goes To …

Howard S. Coleman (Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.), A. Francis Turner (Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.), Harold H. Schroeder (Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.), James R. Benford (Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.) and Harold E. Rosenberger (Bausch & Lomb Optical Co.) for the design and development of the Balcold projection mirror.

Focusing on another problem — the reduction of heat generated during motion picture film projection — Francis and his group developed a successful commercial project known as the "Balcold mirror," that transmitted the infrared while reflecting the visible region of the spectrum.

Film stock was highly flammable and fires in projection booths at cinemas were a frequent occurrence. This thin-film-coated mirror immediately reduced the amount of heat passing through the film in the gate, and minimized the fire hazard. For this contribution, Francis and his group won a Technical Oscar from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1960.

Retirement and Beyond

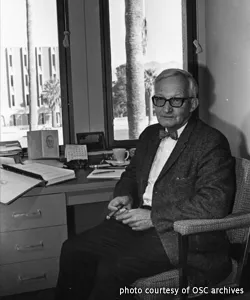

(l to r): Stephen F. Jacobs, Arthur Francis Turner, John Poulos, unknown, and Dean McKenney (OSC's first Ph.D. graduate, 1969.)

Francis retired from B&L in 1971 — but did not retire from optics. He accepted a professorship in Arizona at the Optical Sciences Center (OSC), where he had already served as a visiting professor for several years.

It was an unmistakable sign. The scent of cigars gradually percolating through the ventilating system meant only one thing — Francis was in his office. His cigars, [along with his bowties and cheerful personality], were legendary — as well as his enormous collection of minerals, bugs and optical parts — [all neatly tucked away in his many cigar boxes]. (Angus Macleod, "OSCillations," June 1996)

Until 1979, when Francis retired from the University of Arizona as Professor Emeritus, his research focused on formulation of glass compositions for evaporated thin-film waveguides, precision lens development for integrated optics, and multilayer thin-film waveguide systems

Legacy

Communicating and teaching, largely through personal contact, Francis Turner maintained a lifelong dedication to optical physics. He holds an internationally recognized position in the history of the design of multilayer coatings and their application to practical problems, as well as 24 patents in films and optics.

Honors

- Technical Oscar, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 1960

- President, OSA, 1968

- Frederic Ives Medal, OSA, 1971

-

Doctor of Science, honoris causa, University of Arizona, 1993

Author's Note

Many thanks to OSC Professor Emeritus Angus Macleod and Len Mott, M.S., 1971 for sharing their stories of Francis Turner with me. Through their remembrances, I developed an immense respect for Dr. Turner and his many achievements.

[Editor's Note: Leonard P. Mott, M.S., 1971 made a generous donation to dedicate the OSC Thin Films Laboratory in honor of Arthur Francis Turner, his mentor and friend – a true testament to Francis's "extraordinarily generous [nature] in sharing his knowledge and his eye-witness accounts of the pioneering days in this area of optical technology that he helped create."]